In the modern metropolis of Mumbai, right next to the traffic congested western express highway, there exists a portal to the ancient world of Buddhist monks, a group of caves known as Kanheri caves. The compound consists of 109 caves with several sculptures and stupas carved on the basalt rock during the course of 1st and 10th century CE. The caves give vivid evidences of the world these monks lived in, and the world they interacted with. The world Kanheri comes from the Sanskrit Krishnagiri, which means "black mountain". This

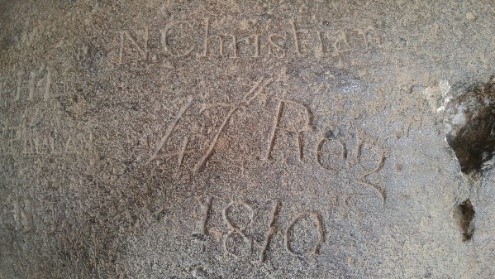

Right near the entrance of this cave, cave # 2 consists of a stupa and several sculptures and three stupas carved sometime between 2nd to 3rd century CE. One of these stupas is larger than the others. On this beautifully polished stupa, some graffities are carved. One of them reads:

“N. Christian

47th Reg.

1810"

Graffiti of N. Christian on Kanheri Stupa # 2

Such graffities are among the most reprehensible things one can do to a heritage structure. But with the passage of time, all deeds – good and bad – become a part of the scroll of history. Now that two hundred years have passed, that ugly scribbling is also part of history. A wandering mind gets curious about this vandal was and what was his story.

Thankfully we live in the information age, and it is amazing what the internet can dig up if one has a strong enough itch to find out. An obscure book ‘MANX WORTHIES OR BIOGRAPHIES OF NOTABLE MANX MEN AND WOMEN’ published in 1901 by A. W. Moore provides the full form of N. Christian – Nicholas Christian, and his place of origin – Isle of Man.

Isle of Man is a small island between England and Ireland. Politically, this place is not a part of the United Kingdom or Great Britain. It is a British crown dependency. The island has a population of 84000 right now. It is safe to assume that the population would have been much smaller in 1810. Nicholas Christian wouldn’t have known many people around him in the British army who came from his native place and who could speak his language – Manx. The rapid expansion of the British Empire, the revolutionary war in the US and the Napoleonic Wars in Europe had stretched British Army far and thin.

Online ancestry records give us the details of the rest of his family. He was the fourth of the ten children of Rev. John Christian (1761-1815) and Elizabeth Martin (1755-1808). We also get Nicholas’s year of birth - 1790. At the time of his visit to Kanheri, he must have been 19 or 20 years old. He was the third of John and Elizabeth’s ten children – Catherine, Anne, John, Nicholas, William, Elinor, Robt, Elisa, Those and James.

Ancestry records show many people with “Christian” surname in Isle of Man, including some well-known figures in the history of Isle of Man. One William Christian, also known as William Dhone or William the Brown, led the rebellion against the crown in 1651 and became the Receiver General and subsequently the Governor of the island on behalf of the British parliament. After the restoration of British Monarchy, William was arrested and executed by firing squad for high treason in 1663. He became an icon of Manx nationalism in later years. In later years, some people of this surname, and possibly members of this clan, served in the British army. The most famous ‘Christian’ with an Isle of Man lineage was Fletcher Christian, who led the famous mutiny on HMS Bounty in 1789, a year before Nicholas was born.

It is hard to say how Nicholas identified himself, but it is evident that he volunteered to serve in the British army and purchased a commission. ‘47th Reg.’ mentioned in Nicholas’s graffiti stands for ‘the 47th (Lancashire) Regiment of Foot’. This was an infantry regiment raised in Scotland in 1741. In 1810, the first battalion of this regiment was deployed in Mumbai, which explains Nicholas Christian’s presence in that region. The second battalion of this regiment was fighting in the Peninsular War against Napoleon, under the command of Duke of Wellington, Arthur Wellesley. An Irish general of considerable fame was leading British forces against the French forces headed by an iconic Italian general.

More google search brings a somewhat sycophantic letter written by many officers of the 47th Regiment to ‘lieut-col. Coming, commanding left wing, H.M. 47th Reg’. ‘H.M.’ stands for His/Her Majesty’s regiments, i.e. the regiments belonging to the British Army. These were different from the armies maintained by the East India Company. The letter was written in “Demaun” on 17th March, 1809. “Demaun” presumably is a variation of Daman, which was the Portuguese territory at this time. During the Napoleonic wars, Portuguese, the formidable rivals of England in prior centuries had become their junior partners in the war against Napoleon. So much that the Portuguese forces in Portugal were under Wellington’s command and the Portuguese were procuring artillery from Britain. The letter also gives Nicholas Christian’s rank – Ensign, which was somewhat like a second lieutenant in British infantry at that time. This was the junior most rank among commissioned officers.

Uniforms of the 47th in 1804 (Lanc Inf Museum & Harry Fecit MBE TD)

At this time most of the commissioned officers were not recruited on merit, but rather the aspirants had to purchase their commission on availability. Family background played a role. John Christian was a clergyman, a profession with enough respectability to allow his son Nicholas to procure a commission.

It is hard to tell what brought Nichloas Christian, Ensign, 47th Regiment to Kanheri that day. The letter from March 1809 confirms his battalion’s stationing in Bombay Castle. The route between Kanheri Caves to Bombay Castle is covered by thousands of Mumbaikars in their daily commute now, but in those days reaching to Kanheri would not have been that straightforward. The land reclamation of Mumbai had started, but had not been completed in 1810. The landmass which includes Kanheri Caves, was mentioned as Caneri Island in older English literature. In old days a water channel existed right until the caves. It is unknown whether that channel existed until 1819, but N. Christian’s journey to Kanheri would have almost certainly involved travelling through waterways and possibly navigating some swamps.

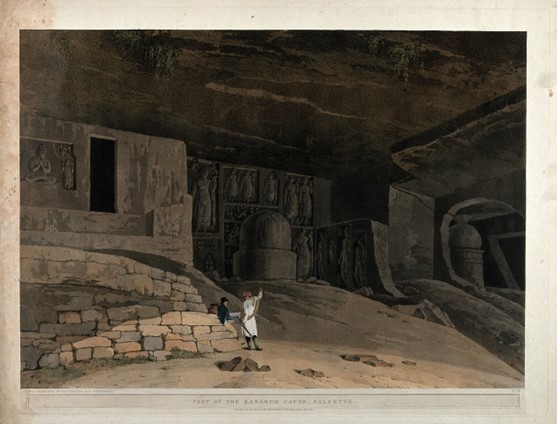

There could be several official and unofficial reasons for a soldier stationed in Bombay Castle to be at Kanheri. It is also possible that officer Christian could have been visiting Kanheri for its archeological attraction. The caves were not exactly unknown at this time. Early British Indologists had already visited these caves and had started documenting its monuments. Europeans were getting curious about Asian antiquities. William Jones had formed the Asiatic Society in Kolkota in 1784 to promote the cause of oriental research. In a different part of the world, Napoleon’s army had famously studied Egyptian treasures during his Egyptian campaign in the preceding decade. Just like Nicholas Christian, the French soldiers had also left their graffiti in Egyptian monuments.

The Kanheri caves on the island of Salsette, near Bombay, Maharashtra.

Coloured aquatint by Thomas and William Daniell, 1800.

The list of unofficial reasons would be long. There were strict rules against soldiers venturing out of the castle without permission. Life expectance of the British in Mumbai was very low, less than half survived two monsoons. Reasons of death, besides warfare, included waterborne/airborne diseases, venereal diseases, heat strokes, food/alcohol poisoning, alcoholism and many others. Alcoholism was a major problem and unsupervised ‘punch houses’ tempted soldiers outside the garrison. Other commonly known temptations for soldiers – prostitution and gambling dens also existed in plenty in the rapidly developing Mumbai. Venereal diseases were rampant and caused more attrition in the European armies than what is commonly acknowledged. In order to mitigate these risks, stringent controls were exercised on the garrison, which attempted to reduce the soldiers’ exposure to outside life.

In the course of military logistics there are countless other reasons why Nicholas could have been ordered to visit Kanheri. His battalion was stationed in India between the 2nd and 3rd Anglo-Maratha wars. His regiment would later go on to participate in the 3rd one, without him. At this time the British and the Marathas lived in an uneasy proximity in Mumbai in a politically fluid scenario. Even between the 2nd and 3rd war, there were plenty of reasons for a soldier to get killed in action.

The date of Nicholas Christian’s presence indicates that most likely he had survived two monsoons in India. This would significantly improve a soldier’s odds of survival in India, as he would have acquired precious immunity against common diseases. But it seems like Nicholas didn’t survive much long. Ancestry records tell us that he died in 1815. Unfortunately, we don’t know how he died. It would be great to close this story with more details, but for now this is as much as we know about that ‘Vandal of Kanheri’.